Foto: Eva-Lotte Hill

42: Wie definieren Sie, Herr Dr. Gehrig, als Historiker Terrorismus?

Sebastian Gehrig: Eine schwierige Frage! Da gibt es verschiedene Auffassungen. Für mich führt eine der jüngeren Erklärungen am weitesten, die Terrorismus als Form politischer Gewalt und als eine Art von politischer Sprache betrachtet. Kommunikationswissenschaftler haben sich sehr intensiv damit beschäftigt, wie terroristische Gruppierungen – sei es ethnischer Natur, Linksterroristen oder auch islamistische Terroristen – sich der Gewalt bedienen, um gewisse politische Forderungen oder Nachrichten zu kommunizieren. Davon hängt ab, welche Art von Anschlägen von terroristischen Gruppen gewählt, wie sie vorbereitet und wie sie inszeniert werden.

42: Also Terroristen als Sender einer Botschaft. Wie steht es um die Reaktionen auf diese Botschaft?

SG: Dafür muss man Fragen stellen wie: Wer fühlt sich von Terrorismus angesprochen? Welche Arten von Reaktionen bringt er in der Bevölkerung hervor? Wie reagiert der Staat? Nicht nur in Bezug auf polizeiliche Gegenmaßnahmen, sondern auch bezogen auf die Darstellung der Terroristen. Wie versucht man dem Terrorismus jegliche Form von Legitimität abzusprechen?

42: Würde sich dieser kommunikationstheoretische Ansatz zum besseren Verständnis grundsätzlich anbieten, da er Terrorakte erst einmal nicht wertet?

SG: Ich denke schon, denn der weiterführende Gewinn ist, dass man sich nicht sofort in den Handlungslogiken von Terroristengruppierungen und reagierenden Staaten verfängt. Besonders als Historiker ist dieser Ansatz wertvoll, wenn man Geschehnisse rückblickend untersucht. Wenn wir die Motivation einzelner, die in den Terrorismus abgleiten und sich dieser Art von politischer Gewalt verschreiben, gar nicht erst verstehen wollen, dann kann man den Gründen nicht näherkommen. Wir als Historiker wollen verstehen, warum Menschen in gewissen historischen Momenten terroristische Handlungsakte persönlich als legitim betrachten.

42: Ihr Forschungsschwerpunkt ist der Linksterrorismus in Deutschland der 70er-Jahre. Was sind die Gründe für diesen Linksterrorismus?

SG: Als historische Antwort wird meist und auch richtigerweise die unzureichend aufgearbeitete nationalsozialistische und faschistische Vergangenheit Deutschlands und Italiens nach dem zweiten Weltkrieg angeführt. Das ist es auch, was die moralische Entrüstung und Legitimität für Linksradikale liefert, die sich zunächst in den späten Sechzigern durch Studentenproteste politisch sozialisieren. Nachdem diese Proteste dann abebben und der soziale Rückhalt innerhalb der radikalen Arbeiterklasse abnimmt, driften bestimmte Leute in die Radikalität ab. In Deutschland und Italien sind das vor allem die Rote Armee Fraktion (RAF) und die Roten Brigaden. Das geschieht vor allem in Norditalien, in Bologna oder Mailand, oder auch in West-Berlin oder Frankfurt. An diesen Zentren sieht man, dass der Linksterrorismus ursprünglich eine lokale Geschichte ist. Es war vielen späteren Terroristen wichtig, das verlorene Moment der 68er-Bewegung wiederzugewinnen.

42: Warum greifen junge Menschen in Deutschland der 70er-Jahre zur Waffe?

SG: Zwei Dinge haben das ermöglicht. Zum einen der noch immer in Teilen als faschistisch angesehene Staat und die noch unzureichend aufgearbeitete NS-Vergangenheit als moralische Legitimation dafür, den Protest mit bewaffneter Gewalt aufzuladen. Zum anderen spielen Netzwerke eine wichtige Rolle. Zunächst sind da die stark ausgeprägten westdeutschen und italienischen Netzwerke in den späten 1960ern, die eine gewisse Verbindung zum Nahen Osten ermöglichen. Die erste Generation der RAF fährt in dieser Zeit zur Ausbildung an der Waffe in den Libanon, sodass eine neue Stufe der bewaffneten Radikalität entstehen kann. Beide Punkte, Legitimation und Netzwerke, sind wichtig, um zu erklären, warum junge Menschen um 1970 in die bewaffnete Gewalt abgleiten. Man muss also sowohl die 68er-Bewegung sehen, aber eben auch diese lokalen und persönlich bedingten Netzwerke betrachten. So konnten sich Menschen zusammenfinden, die die politische Lage in Europa ähnlich beurteilten und dann gemeinsam in die Radikalität abdrifteten.

42: Haben die Mitglieder von Gruppen der RAF oder der Bewegung 2. Juni ihre Handlungen selbst als terroristische Akte verstanden?

SG: Ich denke, dass sich terroristische Gruppierungen nie selber als Terroristen sehen. Sie begreifen ihr Handeln als eine Form von politischem Freiheitskampf für eine gewisse Sache. Die Selbsteinschätzung der RAF und der Bewegung 2. Juni ist da nicht anders, wobei sich die Bewegung 2. Juni vor allem als militanter Arm der lokalen Szene im West-Berliner Milieu verstand und weniger als westdeutsche terroristische Gruppierung. Schaut man sich die programmatischen Schriften der RAF an, wird deutlich, dass sie von Anfang an einen deutlich höheren ideologischen Anspruch hatte und versuchte, die Befreiungskämpfe der Dritten Welt zu unterstützen. Man verstand sich sozusagen als fünfte Kolonne des Befreiungskampfes der Dritten Welt in der Tradition von Vietnamkriegsgegnern. Außerdem bediente man sich einer Sprache des radikalen Maoismus nach dem Vorbild der damaligen Volksrepublik China, um zu legitimieren, warum es überhaupt sinnvoll ist, in einem doch sehr friedvollen, Stabilität ausstrahlenden Westeuropa plötzlich zu so radikalen politischen Mitteln zu greifen.

42: Wenn es von Anfang an um Solidarisierung mit Befreiungskämpfen der Dritten Welt geht, warum wählte man dann Deutschland als Anschlagsziel?

SG: Die RAF wollte die Befreiungskämpfe der Dritten Welt dahingehend unterstützen, dass sie die Bundesrepublik als Helfershelfer der USA und imperiale und kapitalistische Hegemonialmacht angriff. Das geht aus den Bekennerschreiben der ersten Generation klar hervor. Die zweite und die dritte Generation änderte ihren Ansatz stark hin zu einer selbstbezogenen Perspektive, die vor allem darauf drang, gefangengenommene Mitglieder wieder frei zu pressen. Der weltpolitische Anspruch wird dabei zwar rhetorisch aufrechterhalten, wenn man sich jedoch die Aktionspotentiale, die Aktionsziele und -arten ansieht, wurde die tatsächliche Umsetzung dieser ideologischen Agenda nach der ersten Verhaftungswelle 1972 stark zurückgeschraubt.

42: Gab es so etwas wie ein langfristiges Ziel?

SG: Das ist eine gute Frage, da der Linksterrorismus vor allem in der Bundesrepublik eher unspezifisch ist. Es bleibt nebulös, wohin dieser Kampf gegen das faschistische Bonner Regime und die imperialistischen USA denn eigentlich führen sollte. Die meisten Anhaltspunkte sieht man vielleicht noch in der frühen politischen Radikalisierung als Teil der Studentenbewegung um 1967–69, in der viele Spielarten sozialistischer und kommunistischer Revolutionen diskutiert werden. Jedoch bleibt die RAF als terroristische Gruppe ab den 70er-Jahren eine Antwort darauf schuldig, was sie eigentlich will. Das bedingt auch, dass die Unterstützung für die RAF nicht nur in der weiteren Gesellschaft, sondern eben auch im eigenen linksradikalen Milieu rapide abnimmt. Das ist wohl einer der größten Schwachpunkte des Linksterrorismus von Anfang an, dass es keine klare Zielrichtung gab, was man am Ende erreichen wollte.

42: Aus welchen sozialen Schichten rekrutieren sich denn die Terroristen?

SG: Es ist sicher richtig und auch emblematisch für den westdeutschen Linksterrorismus, dass vor allem die Köpfe der ersten Generation immer als gut situierte Bürger und vor allem die Frauen als Bürgertöchter wahrgenommen wurden. Letzteres war für die bundesdeutsche Gesellschaft der 70er-Jahre ein Schock. Die einzige Ausnahme ist natürlich Andreas Baader, dem oft ein halbproletarischer Hintergrund zugeschrieben wird. In einer Art Bürgerschrecknarrativ wird das so dargestellt, als ob diese jungen Studentinnen und intellektuellen Frauen – vor allem Ulrike Meinhof und Gudrun Ensslin – von Baader zum Terrorismus verführt werden. Das sagt auch viel über die westdeutschen Geschlechterdiskurse in den 70er-Jahren aus. Die Frage ist zunächst: Wer ist in dieser Zeit überhaupt Student in Westdeutschland? Wir befinden uns nämlich noch vor der sozialdemokratischen Bildungsexpansion, in deren Zuge verstärkt Arbeiterkinder an die Universität kommen. Der Hauptgrund, warum die führende erste Generation vor allem gutbürgerlichen Hintergrund hat, ist sicher darin zu suchen, dass eben die Universitätslandschaft und auch die Studentenbewegung in Westdeutschland doch stark von der bürgerlichen Mittelklasse geprägt ist, was sich proportional auch in den Mitgliedern der RAF widerspiegelt. Das gilt zumindest für die erste Generation.

42: Und die zweite Generation der RAF?

SG: Nach der Frankfurter Kaufhaus-Brandstiftung 1968 bringen sich Baader, Ensslin und Meinhof verstärkt in Kinderheimarbeit ein und kommen so in Kontakt mit Jugendlichen aus ganz anderen gesellschaftlichen Verhältnissen, die dann stark die zweite Generation der RAF formen. So kommen auch die gewissen sozialen Unterschiede zwischen den RAF-Generationen zustande.

42: Kommen wir nun von der Soziologie der Täter zu der Soziologie der Opfer – Wer waren sie?

SG: Wenn man sich die erste große Welle von Anschlägen 1972 ansieht, richtete sie sich zum einen gegen amerikanische Basen. Andererseits gab es einen Anschlag auf das Springerhaus in Hamburg, wo vor allem Angestellte in der Herstellung zu Opfern werden. Das heißt, die RAF trifft mit einem ihrer ersten Anschläge auch die Arbeiterklasse. Das alles führt zu sofortiger Ablehnung der RAF in weiten Gesellschaftskreisen. Da sieht man wieder, wo die Probleme der RAF liegen: in der Auswahl der Ziele und in der Legitimität. Die Ablehnung wird umso stärker, desto mehr Menschen zu Opfern werden, etwa bei den zahlreichen Polizeikontrollen, wo dann auch Polizisten Schusswechseln zum Opfer fallen.

42: Wer sollte denn eigentlich getroffen werden?

SG: Die intendierten Ziele sind am Anfang stark symbolisch. Die RAF wählte 1972 Ziele wie das Springerhaus, um die vermeintlich faschistisch kontrollierte westdeutsche Presse anzugreifen, aber auch Individuen, die man als symbolisch für den westdeutschen Staat betrachtet. Ein bekanntes Beispiel wäre die Schleyer-Entführung oder bereits 1974 die versuchte Entführung des Richters Günter von Drenkmann, der dabei erschossen wird. Das zeigt, dass sich der ideologische Referenzrahmen der RAF doch stark und schnell verkleinert und zwar von diesen symbolischen Zielen, die noch in den Diskussionen der Studentenbewegung und des Linksradikalismus der späten 60er-Jahre verhaftet sind, zu einem strategischen Terrorismus, der gezielt Führer des Staates und des Finanzkapitalismus auf die Agenda setzt. Man sieht deutlich eine ideologische Verknappung, die von der ersten zur zweiten Generation der RAF stattfindet.

42: Was halten Sie von dem Mythos, dass es auf Seiten der Studierenden erhebliche Sympathien gegenüber der Roten Armee Fraktion gab?

SG: Bis zum Ende der 70er-Jahre gibt es ein diffuses Gefühl der Solidarität mit der RAF unter linksradikalen Aktivisten. Die Gegenstände des Aktivismus haben sich geändert, etwa hin zum Anti-Atom-Protest. Dabei machen viele Aktivisten Erfahrungen mit Polizeigewalt, woraufhin sich auch einige Studenten radikalisieren. So kommt es zu einem Wechselspiel von Gewaltauslösung auf beiden Seiten, das oft auch von staatlicher Seite provoziert wird. Man befindet sich in einer Situation, in der man auch selber möglicherweise Opfer polizeilicher Gewalt geworden ist, wodurch ein Solidaritätsgefühl mit anderen entsteht, die auch vom Staat misshandelt werden. Was sicher am Wichtigsten für die RAF ist – und die RAF-Führung ist da sehr geschickt –, ist ein gewisses Solidaritätsgefühl innerhalb des eigenen Milieus am Leben zu halten, zum Beispiel durch die Idee, dass Linksterroristen gezielt in westdeutschen Gefängnissen gefoltert und misshandelt werden. Da sich die RAF als Gefangene in Isolationshaft inszeniert, bleibt eine Grundsolidarität mit der terroristischen Gruppe, obwohl Terrorismus meistens als politisches Mittel abgelehnt wird. Es gibt also ein ambivalentes Spiel, das die RAF geschickt bedient. Auch mit berühmten, internationalen Gästen wie Jean-Paul Sartre, der die führenden RAF-Mitglieder in Stammheim besucht, wird eine Beziehung zwischen dem linksradikalen Milieu und der RAF am Leben erhalten. Das ändert sich im sogenannten deutschen Herbst 1977, als sich das linke Milieu in überwältigender Mehrheit offiziell dazu bekennt, dass man Linksterroristen nicht in dieser ambivalenten Solidarität unterstützen und begleiten darf, sondern Terrorismus offensiv als politische Strategie ablehnen sollte.

42: Wie würden Sie das dominante Gefühl der Mehrheitsgesellschaft in Bezug auf die RAF beschreiben?

SG: In der Bevölkerung dominiert das Gefühl der Angst. Es gibt da sicherlich unterschiedliche Wellen. Hochphasen sieht man vor allem 1972 mit der ersten Anschlagschwelle und 1975 mit der Lorenz-Entführung und dann zuletzt noch einmal 1977. Es herrscht natürlich auch ein gewisses Alltagsgefühl, in einer bedrohten Gesellschaft zu leben. Das heißt konkret, dass man sich in Städten wie Karlsruhe oder Bonn daran gewöhnt, dass es feste Polizeikontrollen gibt. Dieses ungefilterte Gefühl wird durch die politische Konfrontation zwischen der SPD-Regierung und der CDU verstärkt und durch die Medien natürlich noch einmal zusätzlich befeuert, die ein stereotypes Bild der Linksterroristen zeichnen. Es gibt aber auch zunehmend Gefühle der Angst im linken Milieu selbst, weil Solidarität mit Terroristen von befreundeten Genossen eingefordert wird. Der bekannteste Fall, in dem diese erzwungene Unterstützung in einem Mord endet, ist die Enttarnung eines Informanten des Verfassungsschutzes, der gezielt in einen Hinterhalt gelockt und erschossen wird. Es herrscht Angst davor, dass irgendwann mitten in der Nacht geklingelt wird und ein Freund, der sich radikalisiert hat, vor der Tür steht und um Asyl bittet. Es gibt also ein Bedrohungsgefühl, dass man vielleicht selbst in diese Terrorismusgeschichte hineingezogen wird.

42: Gab es eine Art subkulturelles Kokettieren mit diesem Extremismus? Einen „radical chic“ der RAF, der letztendlich einfach auch modisch war?

SG: Das trifft für das breitere Milieu der Phase von 1967 bis 1970 zu, da noch nicht abzusehen war, welche persönlichen und weiterführenden Konsequenzen die Bewaffnung haben würde, die ja letztendlich zu realer Gewalterfahrung und auch Gewaltausübung führte.

Eine wichtige Rolle bei der Entstehung des Terrorismus spielte die romantische Assoziierung mit den Befreiungskämpfen der Dritten Welt, die tief bis in die Kleidungs- und Musikstile der Zeit hineinwirkte. 1968 war ein Protestjahr, das nicht zuletzt auch über mediale Zusammenhänge funktionierte, die der radikalen Linken das Gefühl gaben, dass es da draußen Gleichgesinnte gibt, die zwar möglicherweise unterschiedliche politische Ziele haben, sich aber gleich anziehen und zudem in eine ähnliche politische Sprache kleiden. Dieser Sehnsuchtsort einer imaginierten Dritten Welt als Gegenentwurf einer mitunter drögen westdeutschen Gesellschaft war entscheidend für den Beginn des Terrorismus. Diese gefühlte Verbindung mit einem Kollektiv führte dazu, dass sich viele nicht nur individuell, sondern auch als Gruppen radikalisierten. Das Bestreben einzelner, sich innerhalb dieser Gruppen als Wortführer zu profilieren, hat sicherlich seinen Teil zum Fortschreiten der Radikalisierung und zum Abdriften in die Abwärtsspirale der politischen Gewalt beigetragen.

42: Was bedeutete das Erstarken des Terrorismus für die junge Bundesrepublik, insbesondere für die damals regierende SPD?

SG: Neben der Ostpolitik war der Linksterrorismus eines der Hauptprobleme der sozialliberalen Regierung. Die konservative Opposition unter der Führung der CDU versuchte von Anfang an, diese Formen der politischen Gewalt als Folge der Reformpolitik der SPD darzustellen und somit die Regierung unter Willy Brandt (1969 –1974) zu delegitimieren. Brandt war während des Zweiten Weltkriegs im Untergrund für die Sozialistische Arbeiterpartei Deutschlands (SAPD) aktiv und wurde stark mit seiner kommunistischen Vergangenheit assoziiert. Gleiches gilt für den damaligen Fraktionsvorsitzenden Herbert Wehner. Führende Persönlichkeiten der SPD werden im öffentlichen Diskurs mit dem Linksterrorismus verknüpft. Hinzu kommen Vorwürfe, dass das Reformprogramm der SPD und die Lockerung sozialer Normen zumindest indirekt den Radikalismus unterstützt haben. Die Vorwürfe trieben die SPD zu drastischen Gegenmaßnahmen, insbesondere zum sogenannten Radikalenerlass von 1972. Demzufolge durften Individuen, die „kommunistischer Umtriebe“ verdächtigt wurden, nicht mehr zum Lehrerberuf oder zu Tätigkeiten im öffentlichen Dienst zugelassen werden, was damals auch noch die Post und die Bundesbahn betraf. Der Kreis der Betroffenen war entsprechend groß. Mit dieser illiberalen Gesetzgebung gab die SPD-Regierung dem innenpolitischen Druck nach. Die Debatte um innere Sicherheit betraf also von Anfang an nicht nur im engeren Sinne die RAF, sondern auch das vermeintlich unterstützende Milieu, zu dem aus konservativer Sicht auch die SPD-Spitze selbst, sowie führende Linksintellektuelle gehörten.

42: Was beendete die Ära des Linksterrorismus? Handelt es sich letztendlich um einen Fahndungserfolg der Behörden oder gab es andere Gründe?

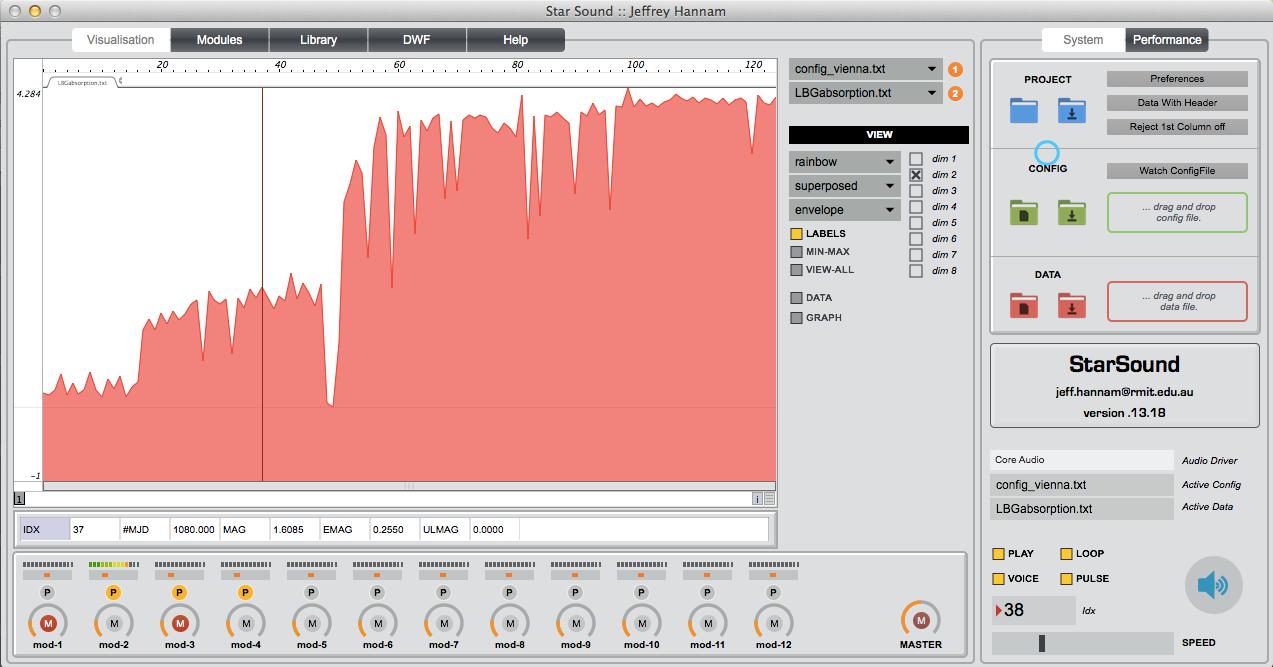

DG: Das Ende des Linksterrorismus als Fahndungserfolg zu bezeichnen würde zu kurz greifen. Sicherlich entwickelte sich das Bundeskriminalamt zur führenden Bundespolizei in Westeuropa, nicht zuletzt, weil hier bereits früh auf Digitalisierung gesetzt wurde. Die rapiden staatlichen Gegenmaßnamen, die auf Computertechnologie basieren – die Frühformen digitaler grenzübergreifender Verfolgungsinstrumentarien – führten dazu, dass viele Terroristen bereits kurz nach Anschlägen verhaftet wurden. Relativ früh nach der sogenannten Mai-Offensive 1972 der RAF waren die führenden Zirkel bereits verhaftet. Der Staat stellte hier und auch während späterer Offensiven seine Handlungsfähigkeit unter Beweis, wobei der Deutsche Herbst 1977 den Umständen entsprechend glücklich verlief, da die Befreiung der Lufthansamaschine Landshut in Mogadischu ohne zivile Opfer von statten ging. Eine gescheiterte Befreiung wäre symbolpolitisch ein Desaster gewesen und hätte wohl eine Staatskrise nach sich gezogen.

42: Wenn diese erfolgreichen staatlichen Gegenmaßnahmen nicht zum Ende des Terrorismus geführt haben, was war es dann?

SG: Auf lange Sicht war es eher die Abwendung vom Terrorismus innerhalb des linksradikalen Milieus, die dazu geführt hat, dass die RAF in den 80er-Jahren stark isoliert wurde. Wir wissen heute, dass die RAF zunehmend von terroristischen Netzwerken im Nahen Osten und auch von der Hilfe der Stasi und der DDR abhängig wurde, da die eigenen, heimischen Netzwerke nicht mehr funktionierten. Die Erfahrung mit dem Terrorismus und der dazugehörigen staatlichen Gegenreaktion führte zu dem Eindruck, dass die Teilhabe an internationalen Kämpfen das Potential der Linken in Westdeutschland doch weit überstieg. Dementsprechend erlebt linkradikaler Aktivismus im Übergang von den 1970ern zu den 80er-Jahren einen Wandel: er regionalisiert sich, etwa zu lokalen Anti-Atomkraftprotesten an geplanten Kraftwerksstandorten. Andere Aktivisten werden Hausbesetzer oder ziehen sich auf Landkommunen zurück. Die alte Idee, dass man sich erst selbst im kleinen Kreis revolutionieren muss, bevor man die Gesellschaft verändern kann, gewinnt wieder an Zuspruch. Für viele weibliche Aktivistinnen werden der Feminismus und die Frauenbewegung zum primären politischen Bezugspunkt. Diese Diversifikation des Protests ab Mitte der 70er-Jahre in verschiedene Formen des lokalen Linksradikalismus führt zum Verlust der ideologischen Anschlusskraft an weltpolitische Probleme, die 1968 noch im Fokus stehen. Ich glaube, dass diese Entwicklung sehr viel mehr zur Deradikalisierung beigetragen hat, als die erfolgreiche Fahndung nach Terroristen.

42: Auch in jüngster Zeit wird die Fahndung nach Terroristen vor allem als Misserfolg wahrgenommen. Gibt es strukturelle Parallelen zwischen dem damaligen Linksterrorismus und dem heutigen islamistischen Terror?

SG: Die größte strukturelle Ähnlichkeit sehe ich in der Art und Weise, wie Terrorismus gesellschaftlich verhandelt wird. Dieses diffuse Gefühl, dass eine bestimmte Bevölkerungsgruppe als Bedrohung wahrgenommen wird. Heute sind das vor allem muslimische Einwandererinnen und Einwanderer. Die Debatten der letzten Monate um Fahndungsmisserfolge durch behördliches Fehlverhalten haben große Parallelen zu Diskursen in den 70er-Jahren. Denken wir etwa an die vielzitierte Episode, dass die Wohnung, in die Hanns-Martin Schleyer verschleppt wurde, erkannt wird, aber aufgrund eines Verfahrensfehlers bei der Weitergabe der Informationen keine polizeiliche Überprüfung stattfindet. Diese Arten von gesellschaftlicher Wahrnehmung und Verarbeitung terroristischer Bedrohung sind ähnlich wie heute, nur, dass sich eben das Bedrohungssubjekt gewandelt hat. Dabei wird der Terrorismus weniger stark als innergesellschaftliche Gefahr wahrgenommen, sondern eher als etwas, das von außen ins Land dringt, etwa im Zuge der Flüchtlingskrise.

42: Welche Lehren könnte man heute aus den Parallelen zwischen Linksterrorismus und islamistischen Terror ziehen?

SG: Parallelen könnte man zum Beispiel identifizieren, indem man sich ansieht, wann die öffentliche Debatte zu übermäßiger Radikalisierung der Gesellschaft geführt hat und staatliche Reaktionen zu weit gegangen sind. Das betrifft die Frage, welche Rechte Nachrichtendienste haben sollten und wo es bei der Strafverfolgung zu einem Austesten des Grundgesetztes und rechtsstaatlicher Grenzen kommt. Diese wurden in den 70er-Jahren durchaus übertreten, was wiederum die Radikalisierung weiterer Kreise möglicher terroristischer Gewalttäter bedingen kann. Der Unterschied bleibt, dass damals die Bedrohung als aus der Gesellschaft kommend angesehen wurde, während sie heute oft als etwas Externes betrachtet wird. Grundsätzlich können wir jedoch aus der Geschichte des Linksterrorismus lernen, dass im Hinblick auf die Täter auch individuelle und sozioökonomische Beweggründe in den Blick genommen werden müssen.

42: Wie schätzen Sie das Bestehen des heutigen Linksterrorismus in Deutschland ein?

SG: Es gibt zwar immer wieder aufflammende Wellen von anonymem Linksradikalismus vor allem in Berlin und in Hamburg, wo nachts Autos angezündet werden. Nachdem sich die RAF Ende der 1990er offiziell aufgelöst hat, gibt es aber kein terroristisches Netzwerk mehr. Die radikale Linke in Deutschland beschäftigt sich, wenn überhaupt, nur noch mit ideologischen Relikten der RAF-Zeit. Es gibt aber durchaus noch reale Nachwirkungen der RAF selbst, mit denen wir uns beschäftigen müssen. Letztes Jahr kam es zu einem Überfall auf einen Geldtransporter, der mit ziemlicher Sicherheit auf Mitglieder der dritten RAF-Generation zurückgeht. Da es in der Bundesrepublik niemals eine Generalamnestie für Linksterroristen gegeben hat, leben noch heute ehemalige Mitglieder solcher Gruppen innerhalb der deutschen Gesellschaft und halten sich versteckt.

42: Ein bekanntes ehemaliges Mitglied der linksterroristischen Vereinigung Antiimperialistische Zellen (AZ) propagiert heute den radikalen Islam. Der gemeinsame Nenner scheint noch immer der Antiimperialismus zu sein. Gibt es eine Erklärung für solche Übertrittsphänomene?

SG: Die Verbindung von radikalen Linken und islamistischem Radikalismus geht ideologisch betrachtet durchaus auf die 70er-Jahre zurück. Für westdeutsche Linke ist diese Vergangenheit unangenehm. Nach dem Anschlag auf die Olympischen Spiele im Jahr 1972 hat die RAF diesen in einer öffentlichen Äußerung gutgeheißen. Das geschieht in einem Kontext, in dem sich die westeuropäische radikale Linke von Israel abwendet, nachdem sie den Staat in den Jahrzehnten nach 1945 aufgrund der Verbrechen des Holocausts durchaus unterstützt hatte. Je mehr Israel als imperiale Macht im mittleren Osten wahrgenommen werden konnte, vor allem nach dem Sechstagekrieg im Jahr 1967 und der Besetzung des Westjordanlands und des Gazastreifens, kommt es zu einer Umorientierung im radikal-linken Milieu. Diese führt dazu, dass in einer anti-imperialistischen Rhetorik und Logik der Zeit der Staat Israel die Seiten wechselt und als Teil westlicher imperialistischer Kräfte betrachtet wird. Es ist durchaus möglich, dass sich heutzutage noch Altlinke in dieser Denktradition sehen und sich für islamistischen Terrorismus begeistern können. Vor dem Hintergrund der historischen Verantwortung Deutschlands nach dem Holocaust ist dieser starke Antizionismus antiimperialistischer Lesart von Links das wahrscheinlich problematischste politische Resultat der 70er-Jahre, mit dem sich die Linke noch länger befassen muss. Das sind Debatten, die sich bis heute bis in die Parteipolitik hineinziehen. Das Verhältnis zu Israel ist nach wie vor ambivalent.

42: Werfen wir zuletzt noch einen Blick auf Europa. Könnten Sie die Entwicklungen des europaweiten Terrorismus in den 70ern skizzieren?

SG: Wenn man sich die Opferzahlen ansieht, stellen eigentlich die 70er- und 80er-Jahre die Hochzeit des Terrorismus in Europa dar, ganz im Gegensatz zum heutigen Bedrohungsgefühl in den europäischen Gesellschaften. Aufgrund des Lockerbie-Attentats ist 1988 das Jahr mit den meisten Opfern terroristischer Anschläge im europäischen Kontext. Anzahl und Frequenz terroristischer Anschläge – der ETA im Baskenland, der IRA in Nordirland, der RAF in Westdeutschland, der roten Brigaden in Italien und ab den 1980ern auch der Action Directe in Frankreich – waren damals viel höher als heutzutage. Das zeigt, wie stark Terrorismus in der Lage ist, Bedrohungsgefühle auszulösen, die über die eigentlichen Anschläge hinausgehen. Statistisch betrachtet gab es 2004 zwar den Anschlag in Spanien und im letzten Jahr die Anschläge in Frankreich, die sehr viele Opfer gefordert haben. Die Anschläge in Großbritannien im letzten und in diesem Jahr haben dieses Bild natürlich verändert. Parallel dazu haben sich die gesellschaftlichen Potentiale, aus denen diese Bedrohungen kommen, stark verändert. In den 1970ern und -80ern reden wir über ethnisch und politisch motivierte Terroristen, sei es in Nordirland, im Baskenland, in Italien, der Bundesrepublik oder Frankreich. Das löst sich ab mit zunächst wenigen und auch zum Teil unbeachteten islamistischen Anschlägen in Europa, schon in den 70er- und 80er-Jahren. Erst seit dem 11. September werden diese aber als große Bedrohung der öffentlichen Sicherheit wahrgenommen.

42: Folglich ist es religiöser und nicht weltlicher Terrorismus, der heute als vorherrschende Bedrohung wahrgenommen wird.

SG: Das könnte man so sagen, ja.

42: Sie sagten bereits, dass dieser religiöse Terrorismus in der öffentlichen Wahrnehmung eine Bedrohung von außen ist. Ist die Furcht vor innereuropäischem Terrorismus damit Geschichte?

SG: Im Zuge der Brexitdebatte wurde zum Beispiel sichtbar, dass Ängste vor einem erneuten Aufflammen der politischen Gewalt in Nordirland noch nicht so weit entfernt sind, wie wir in den letzten Jahren gedacht haben. Vor dem Brexit im Juli letzten Jahres hätten wir aber nicht darüber geredet. Vor allem nicht im europäischen Kontext. Möglicherweise als innerbritische Debatte. Aber dass sich die französische und auch die deutsche Presse mit dieser Frage beschäftigt, wäre so in diesem Ausmaß wahrscheinlich nicht passiert. Man sieht, dass diese Bedrohungspotentiale sehr schnell wieder öffentlich wachgerüttelt werden können, sollte sich die politische Lage verändern. Das genaue Gegenbeispiel haben wir im Fall der ETA, die vor wenigen Wochen ihre letzten Waffendepots bekanntgegeben und den polizeilichen Autoritäten übergeben hat. Man sieht aber in beiden Fällen, wie langlebig das Phänomen politscher Gewalt in der öffentlichen Debatte ist und wie schnell es wieder in öffentlichen Diskursen mobilisiert werden kann.

Herr Dr. Gehrig, vielen Dank für dieses Interview.

Interview: Jonas Hermann, Lena Kronenbürger